Before delving into the historical significance of the Pakistan Resolution, I would like to share a story that resonates deeply with its journey, a story that I often recount to my students. A father takes his young son to a park and stands before a majestic oak tree. The father asks, “What do you see?” The son replies with a simple observation: “A beautiful, giant oak tree.” The father then adds, “But what you see is only the final form. Beneath the surface, there was a seed, planted in darkness, nurtured by unseen forces, and slowly growing through challenges to eventually burst into life.”

This allegory of the oak tree perfectly captures the spirit of the Pakistan Resolution: a vision that emerged from years of struggle, internal debates, and differences, all united by a singular purpose—the advancement of the Muslim community.

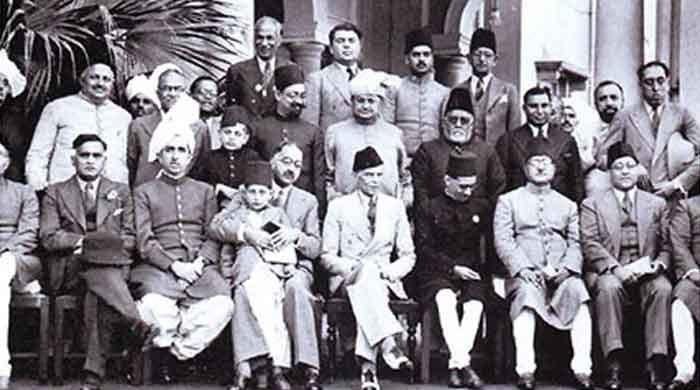

At Iqbal Park in Lahore, in 1940, the seed of Pakistan was sown in the form of the Pakistan Resolution. Yet, like the hidden journey of a seed turning into an oak, the resolution’s road was fraught with turbulence, differences, and challenges that eventually culminated in the creation of Pakistan in 1947.

In the years leading up to the resolution, the Muslim community in India found itself at a crossroads. The attitude of the Congress towards the Muslims was often dismissive and unaccommodating. In a climate where unity was essential, the fragmented voices of the Muslim League, despite their internal differences, were driven by the common goal of securing a future for Muslims in India. Influential figures like Allama Iqbal reinforced this vision in his letters to Muhammad Ali Jinnah in May and June 1937. Jinnah himself later emphatically declared to the Bombay governor, “There is nothing more to do except to establish a state of our own for the Muslims of this country.”

In stark contrast, Mahatma Gandhi’s response to these overtures was evasive. His letter to Jinnah, in which he confessed feeling “utterly helpless” and unable to foresee “daylight” for Muslims in a united India, only deepened the resolve of the Muslim leadership. This episode underscored a painful reality: when the future seemed uncertain and external support faltered, a unified and clear articulation of demands became not only necessary but inevitable.

Historians like Bani Prasad have observed that it was “the fear of the future” that weighed heavily on the Muslim mind in 1937. Faced with the prospect of marginalisation, the Muslim community recognised that unless they formulated their demands clearly and persistently pursued them, their future in India was at stake. Consequently, at the annual meeting of the All-India Muslim League in Lucknow, the idea of establishing “Free Muslim states” in India emerged as the new clarion call—one that resonated deeply with the aspirations of millions.

The transformation of the Muslim mindset did not occur overnight. Exactly a year after the Lucknow session, the Sindh Muslim League, at its conference held in Karachi, took a decisive step towards realising the Pakistan scheme. Renowned historian Reginald Coupland captured the essence of this turning point by noting that, from the autumn of 1938 onward, a new and positive doctrine was taking shape: the belief that Muslims were not merely a “community” but a distinct “nation.”

Jinnah, with his visionary leadership, embraced this evolving sentiment. He not only contemplated the immediate benefits for the Muslim community but also recognised that a united nation would uplift Muslims across India. By engaging with issues such as the Palestine cause, Jinnah underscored his commitment to Pan-Islamism, effectively galvanising support from the broader Islamic world. This blend of Pan-Islamism and nationalism, often referred to as Islamic nationalism, became the heartbeat of the Pakistan Movement, drawing strength from the convergence of diverse ideas and aspirations.

A significant yet underappreciated milestone in this journey was the Meerut meeting of the Muslim League Working Committee on March 25, 1939. The meeting saw provinces being asked to submit their schemes to a subcommittee, an acknowledgment that the vision of Pakistan revolved around the regional aspirations of its people. However, this process also revealed sharp differences in opinion. The debates were intense enough that prominent voices, like the Raja of Mahmoodabad, dismissed Pakistan as “no longer an academic question.” The Muslim community, in its quest for clarity, found itself at a crossroads—diverging on specifics but united in the fundamental belief that unity was essential for survival and progress.

Jinnah’s task was further complicated by the government’s decision to implement federation as enshrined in the Act of 1935. This move led to a split within the Muslim League, jeopardising the emerging Pakistan proposal. With formidable challenges arising from both within and outside the party, Jinnah was forced to marshal all his energies to counter what he perceived as a deliberate attempt to undermine the Pakistan scheme. His efforts underscored a critical lesson: in moments of crisis, the strength of a movement lies in its ability to adapt, overcome internal divisions, and stay true to its core vision.

The Pakistan Resolution, ultimately, was not a product of smooth consensus but the culmination of a prolonged period of strife spanning two and a half years. It underwent numerous transformations, facing myriad pitfalls along the way. Yet, its passage was a testament to a democratic process that, despite unexpected challenges, moved forward only when broad consensus was achieved among the diverse voices of the Muslim community.

The Lahore Resolution, as it came to be known, has been the subject of much debate among scholars and critics. Many argue that its wording was ambiguous, vague, and open to multiple interpretations. Critics point out that the resolution’s text used several synonymous yet overlapping terms—units, regions, areas, zones, and states—to describe “territory.” Historian K.K. Aziz even contends that by enclosing the words “independent states” in quotation marks, the resolution hinted at the possibility of establishing more than one state.

These criticisms have, at times, been invoked by provincial leaders who protest against Pakistan’s highly centralised system and the perceived denial of provincial autonomy. Some even advocate for a confederal administrative setup, arguing that it is more in line with the original intent of the Lahore Resolution. Yet, despite these ongoing debates, one fact remains incontrovertible: the diverse schemes and perspectives were all driven by the same underlying motive—the upliftment and empowerment of Muslims.

In April 1946, a convention of Muslim League legislators in Delhi took a decisive step. They resolved to create a single state, not multiple states. The term “states” was thus replaced by “state,” a subtle yet powerful amendment that ultimately led to the creation of a unified Pakistan on August 14, 1947.

Today, as Pakistan faces its own internal and external challenges, the lessons from the Pakistan Resolution are more relevant than ever. In a world where divisive narratives and differences often threaten collective progress, the history of the Pakistan Resolution reminds us that unity does not always require absolute uniformity. Just as the diverse yet unified efforts of the Muslim League contributed to the emergence of Pakistan, modern challenges call for a similar harmonisation of differences, channeling them towards a common, overarching goal.

#call #revisit #resolution #today